Report | December 14, 2020

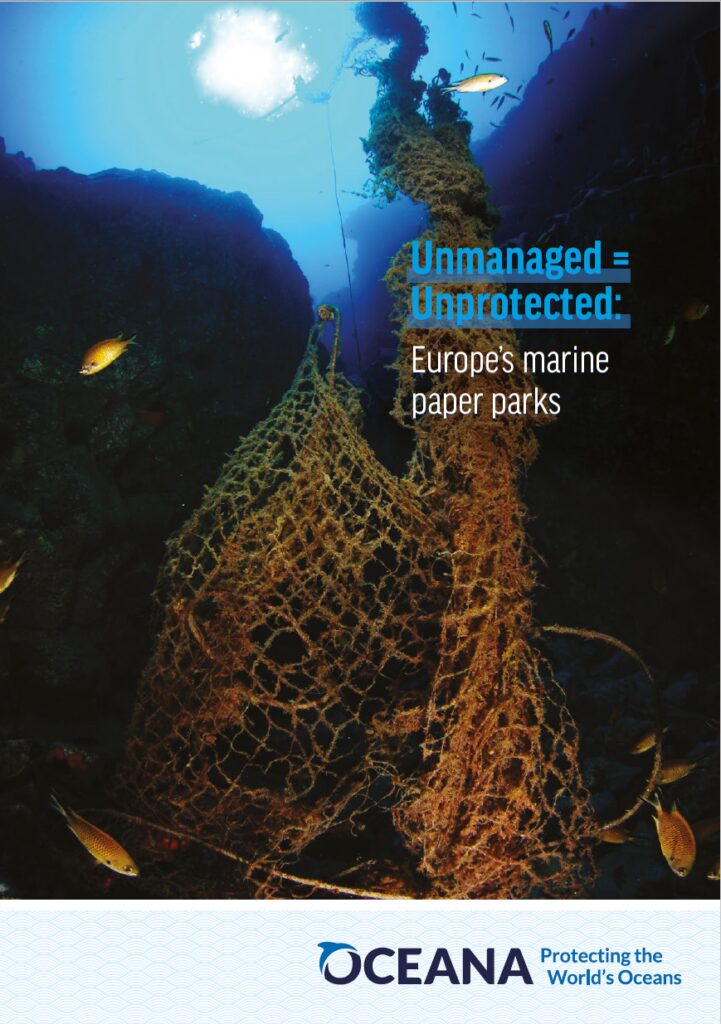

Unmanaged = Unprotected: Europe’s marine paper parks

Visit our online viewer to explore threats in European MPAs in more detail

Executive Summary

In the face of intense human pressure on European seas, a network of well-managed marine protected areas (MPAs) is critical for marine biodiversity protection. In 2018, the EU (including, at the time, the United Kingdom) declared having met international targets for marine conservation, by designating more than 10% of its waters as MPAs. However, this declaration of success ignored the fact that designation is just one step towards achieving real protection. Without effective management, designated MPAs remain mere ‘paper parks’ that provide little to no actual protection.

As the EU and the UK aim towards a more ambitious target of protecting 30% of the ocean, a key question remains: how protected are existing European MPAs? In this report, we address this question from two different angles, considering: 1) the extent of damaging human activities inside MPAs; and 2) whether management plans and measures are sufficient to address these threats.

We first examined the spatial overlap between the largest network of European MPAs (Natura 2000, comprising 3449 MPAs) and 13 human activities that represent direct threats to marine species and habitats in Europe. Our analysis revealed a troubling picture: nearly three-quarters of sites were affected by one or more threats, and those not affected represented a mere 0.07% of the total area of the Natura 2000 MPA network. At the national level, threats were present in more than half of the MPAs in each of the 23 countries analysed. The most widespread threats were maritime traffic and fishing, affecting 66% and 32% of MPAs, respectively. Across the entire network, MPAs faced an average of two threats, with some sites in Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK facing eleven or more threats each.

Focusing on 1945 Natura 2000 MPAs designated specifically for the protection of seabed habitats exposed the extent to which theoretically protected habitats face direct threats. Fifty-five percent of those MPAs were subject to one or more seabed threats, and MPAs with six or even eight (out of a maximum of eight) seabed threats were documented in the waters of eight countries across the Atlantic and Baltic. More than 500 Natura 2000 MPAs designated for seabed habitat protection permitted ‘high-risk’ fishing: fishing with gears that are known to damage those very habitats. Such fishing was so pervasive that only 14% of the total area designated for habitat protection lay within MPAs that were not exposed to high-risk gears. High-risk fishing was particularly prevalent within MPAs that are intended to protect reefs, sandbanks, and Posidonia beds.

In the second part of our assessment, we evaluated management plans from a selection of the largest Natura 2000 MPAs, by country. According to official information provided by countries to the European Commission, management plans were reported to exist for only 47% of the 43 sites assessed. Where management plans did exist, they had often been seriously delayed – leaving sites unmanaged for up to 11 years – and 80% of plans were found to be generally incomplete. Despite establishing clear conservation objectives, most of the assessed plans were characterised by clear weaknesses that hinder the effectiveness of management: a lack of deadlines for implementing measures; a failure to manage specific features for which sites were designated; a failure to address major threats that put those features at risk (like fishing or dredging); and the absence of provisions for surveillance and monitoring.

Our findings help to better understand and quantitatively estimate the scale of the problem of European marine ‘paper parks’, while also illustrating the underlying failures and weaknesses of current MPA management approaches. The intensity of threats, together with weak management of Natura 2000 MPAs raises questions about the very essence of MPAs in Europe: many MPAs aim for just the legal minimum protection for a limited number of features, while permitting damaging activities that are incompatible with wider ecosystem protection and recovery. This situation is further evidenced by the ongoing decline of marine species and habitats inside European MPAs.