Overview

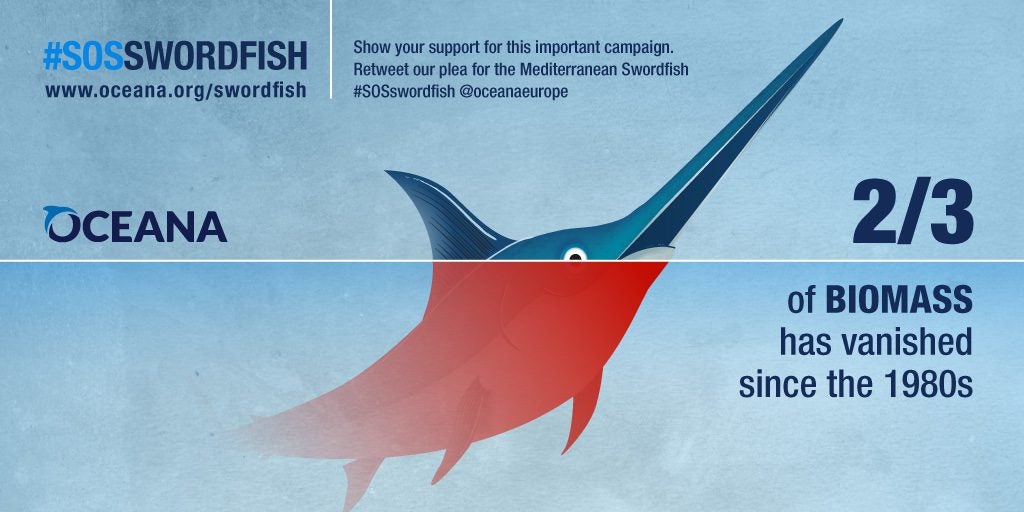

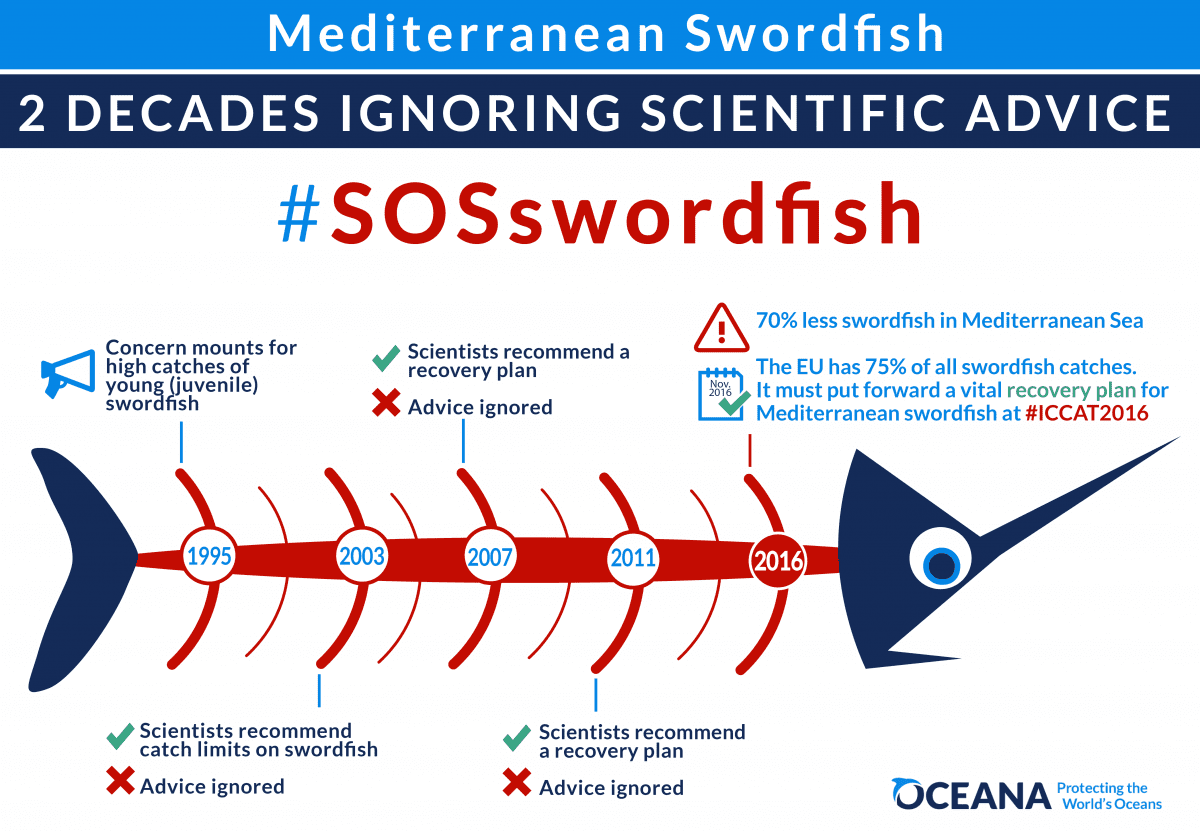

However, the number of a Mediterranean swordfish has plummeted to critical levels. More than 3 decades of overfishing swordfish in this area has left stocks at only 30% in 2016, with no sign of a recovery.

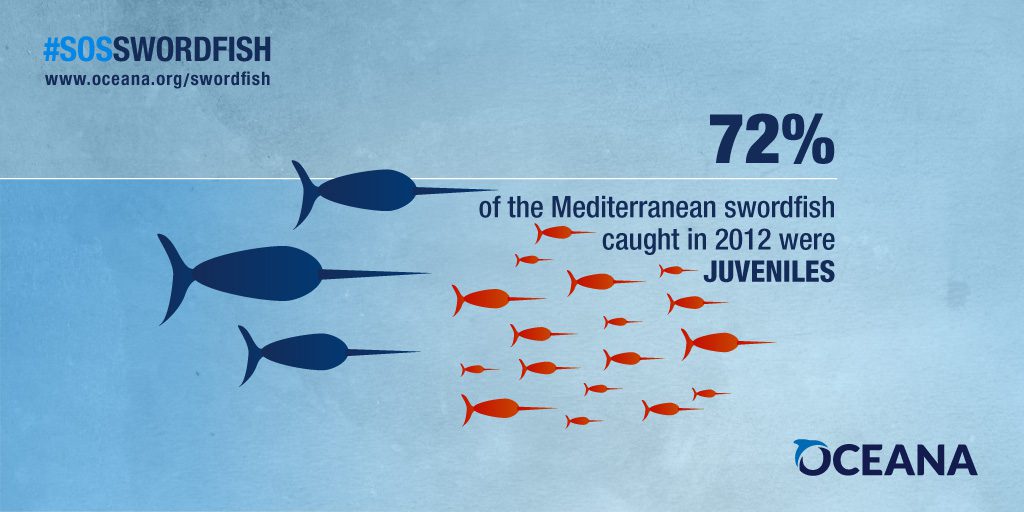

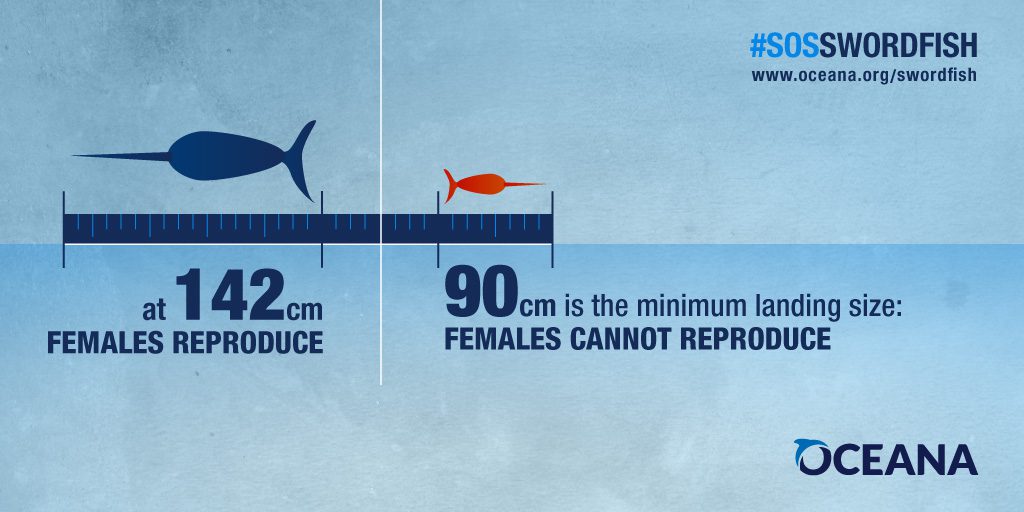

Many swordfish caught in these waters are too young (juvenile, in fishing terms) to be able to reproduce, putting the long-term sustainability of swordfish at great risk.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What are they like?

Mediterranean swordfish (also referred to as SWO MED) are fast swimmers and often travel long distances in pursuit of prey. Unlike other fish of its size, Mediterranean swordfish behave differently; they travel alone, or together with their mate, and not in schools (groups of fish). In fact, some fishermen try to catch a female swordfish knowing that a male is not too far behind her.

How are SWO MED caught?

They are caught in several ways. Some more selectively like (targeting one species and thus not catching other unwanted fish) using a spear-like arrow (harpoon) that is ‘fired’ at the swordfish, but the majority are caught by means of large fishing boats called long liners that are equipped with hooks.

For many years, and particular during the 1980s and mid-1990s, the worst way to fish swordfish, or any fish for that matter, was through driftnets. Since 2007, these huge nets have been banned from use in EU Mediterranean waters for highly migratory species like tuna and swordfish. Then in 2009, ICCAT brought in a complete ban in all Mediterranean waters.

Why are stocks at a critical level in 2016?

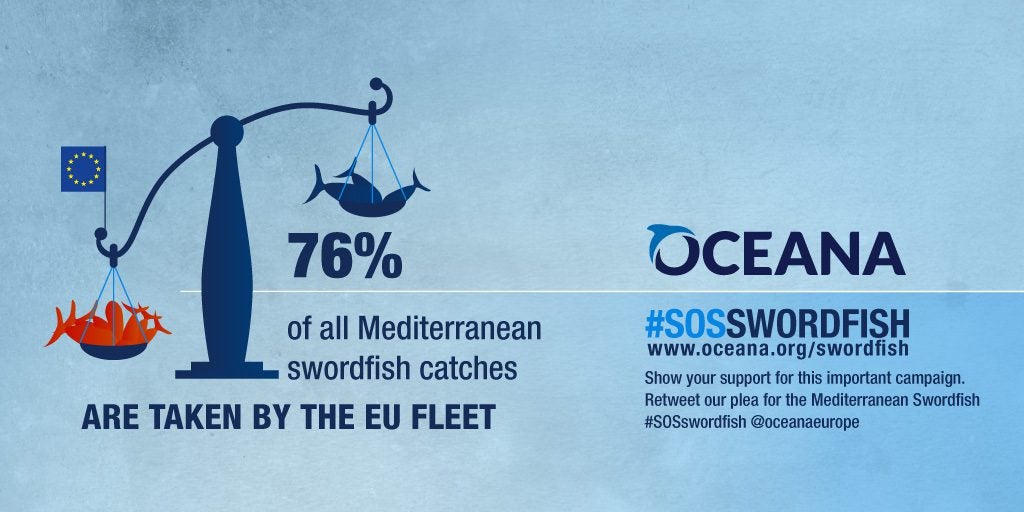

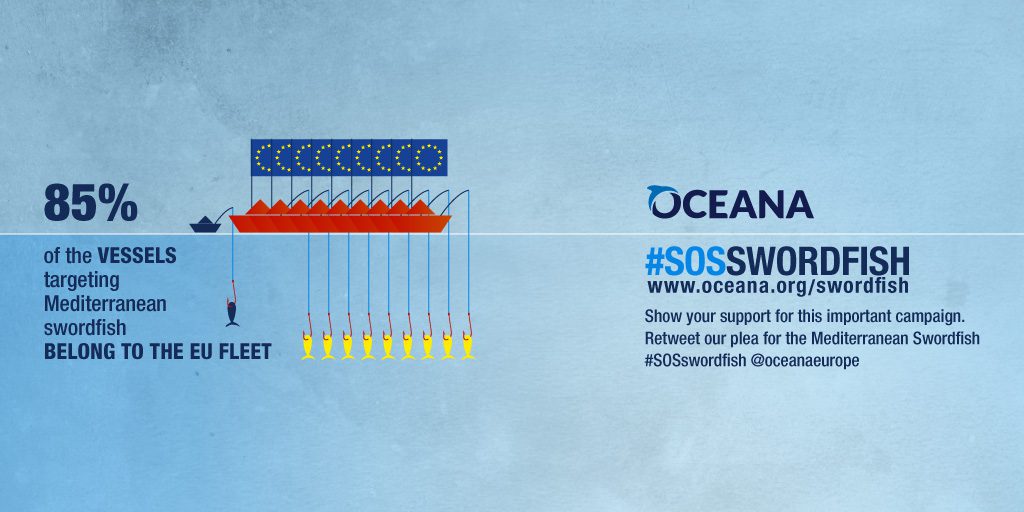

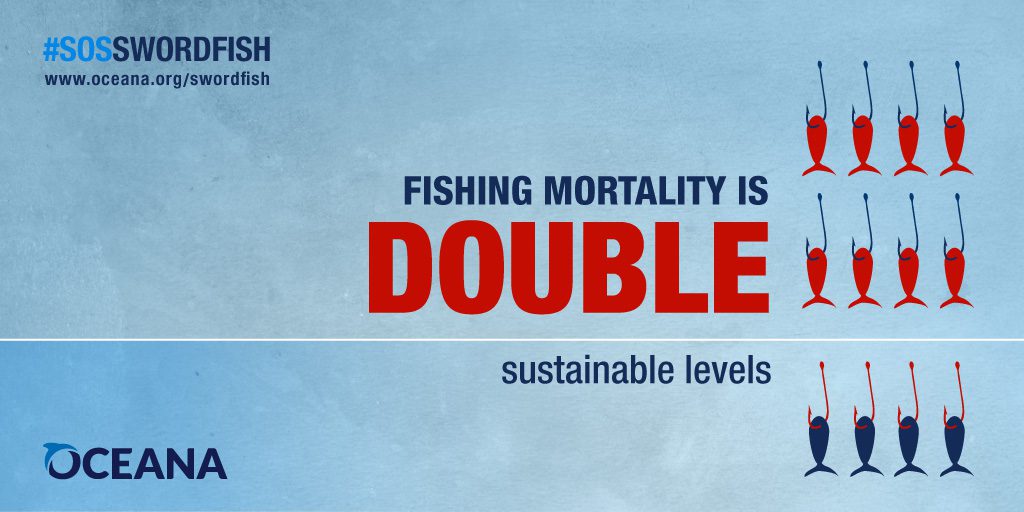

Two factors: thirty years of relentless overfishing swordfish in the Mediterranean Sea has wiped out 70% of stocks, and a chronic lack of a management to fish swordfish sustainably and replenish this highly-commercial species.

Three quarters of the swordfish that end up at habour are too young and too small to reproduce. This is because the current minimum legal catch size for fisherman to legally catch SWO MED is set too low-at 90cm-meaning a biological recovery in swordfish numbers in the Mediterranean is near impossible. This is around 50cm smaller (adult maturity size) than the size recommended by scientists.

How can we put this right?

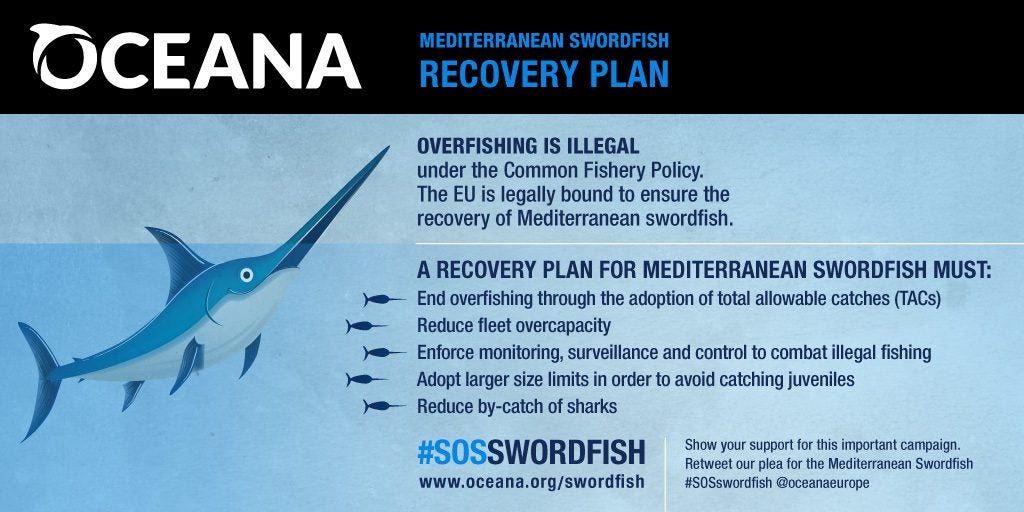

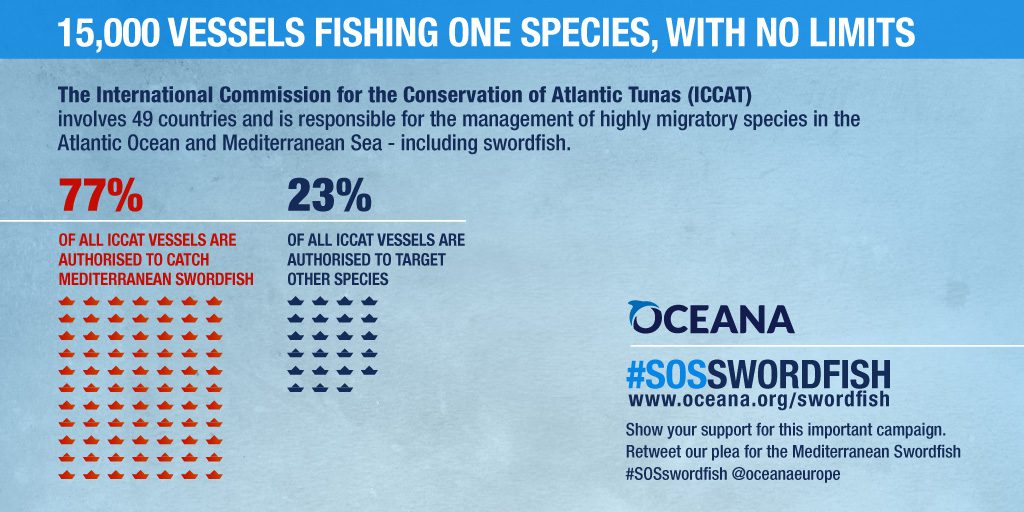

Oceana recommends a series recovery plan that must be agreed and adopted at the ICCAT Special Meeting in November 2016. There, members of ICCAT will assess swordfish stocks and agree on the total amount of swordfish that can be fished for the next two years, also known in the fishing industry as total allowable catches (TACs).

At the 2016 ICCAT meeting, Oceana will campaign for a recovery plan to include:

- Stronger monitoring control and surveillance measures to combat overfishing in the region

- Protecting young, small swordfish (juveniles) by increasing the current catch size limit

- Stopping swordfish fishing in certain times of the year (Sept.-Dec.) to allow the juveniles time to reproduce

- Protecting vulnerable species that get caught in the process of swordfish fishing

For more detailed technical recommendations please see our 2016 Position Paper: Inaction Is not An Option

Oceana acknowledges the generous support of LIFE EU Programme

Oceana acknowledges the generous support of LIFE EU Programme