February 5, 2018

The impact of the IUU Regulation on seafood trade flows

How has the EU action against illegal fishing changed our seafood trade flows? And what do these trade patterns tell us?

Ten years after the adoption of the EU IUU Regulation, a new report examines how the EU’s carding system has impacted the flow of seafood products into and within the EU

Source: EJF, Oceana, Pew and WWF. Author: Victoria Mundy

Just over 10 years ago, it was estimated that 500,000 tonnes of illegally caught seafood products were entering our EU markets every year. An illicit activity valued at 1.1 billion euro that was not only damaging local communities and businesses, but also depleting our pristine marine resources. The European Union is the largest trader of fishery and aquaculture products in the world in terms of value and its citizens consume an average of 25.5kg of fish per capita/per year. This is why the adoption of the EU Regulation against illegal unreported unregulated (IUU) fishing in 2008 was a crucial step to ensure that all fish brought to our table is legally sourced and traded.

The Regulation is arguably the most ambitious law globally to combat IUU fishing using a series of trade-related measures. Its carding system has proven particularly effective at driving fisheries reforms in third countries, in terms of improvements in fisheries management practices and controls over the legality of seafood. According to this system, countries can be warned (yellow-carded) by the European Commission for failing to take action against IUU fishing in line with international standards. Failure to address shortcomings in a timely and effective manner results in a ban on the country’s exports of seafood products to the EU (red-carded), amongst other sanctions, until the necessary measures are adopted. This clearly has an important impact on both the exporting (‘carded’) country and on the EU Member State of import.

Since January 2010 – when the Regulation entered into force – 25 countries have been yellow-carded and of these 3 are still red-carded (see list here).

But what actually happens to seafood trade flows when a country is yellow or red-carded?

The new report, published today by EJF, Oceana, Pew and WWF* in collaboration with TRAFFIC, is the first detailed analysis to show that shifts in seafood import flows have occurred since 2010 that appear directly related to the IUU Regulation. The report focuses on ‘high risk’ trade flows to the EU, in terms of the likelihood that products were caught in contravention of applicable fisheries rules.

Contrary to previous analyses, the report shows that weaknesses in Member State import controls and uneven standards could be providing a route for non-compliant products to enter the EU market.

Most notably, the report identifies several examples of high-risk trade flows shifting among EU countries following the warning (yellow-carding) of certain exporting countries.

Increased imports were, for example, reported by Italy following the carding of over half of the third countries/territories analysed, particularly for high value products such as swordfish and tuna.

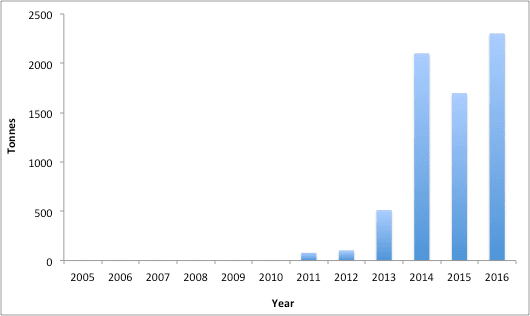

Imports of frozen yellowfin tuna from Ghana* reported by Italy (2005-2016)

Source: Eurostat *Yellow card issued in November 2013, card withdrawn in October 2015

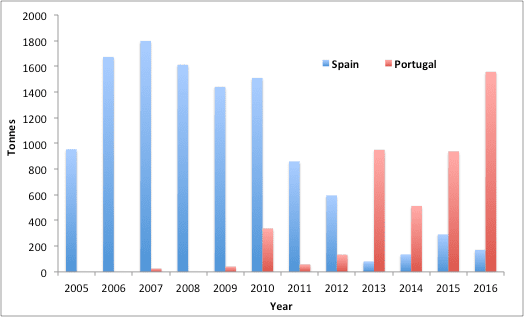

Imports of frozen swordfish from Taiwan, PoC* reported by Italy

Source: Eurostat *Yellow card issued in October 2015, not withdrawn yet.

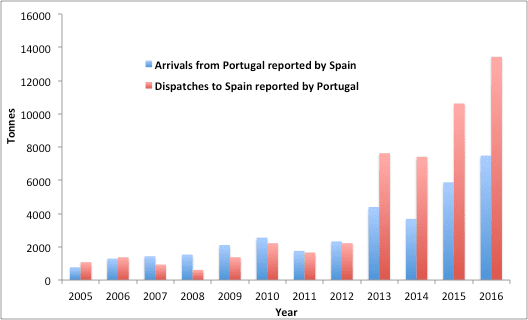

Portugal reported increased imports from several third countries that had been carded, and this often coincided with a decline in imports of the same commodities (swordfish, shark and surimi) reported by Spain. Analysis of intra-EU trade flows also indicates that Portugal may have been used as a point of entry for products destined for Spain, making it difficult for authorities in Spain to check the legal origin of this seafood due to the EU single market.

Imports of frozen swordfish from Panama* reported by Spain and Portugal

Source: Eurostat *Yellow card issued in November 2012, card withdrawn in October 2014

Intra-EU trade* in frozen swordfish from Portugal to Spain

Source: Eurostat *Includes data reported by both Portugal as the Member State of dispatch (intra-EU export), and Spain as the Member State of arrival (intra-EU import)

Random peaks in trade and other trade anomalies were reported also by other EU countries that are not considered major importers of seafood in the EU, e.g. Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

These trends suggest that operators may be exploiting those EU borders that are seen as more porous for the import of high-risk and, potentially, illegally caught seafood. This warrants the urgent need for improved coordination and harmonisation of import controls across Member States.

Transit and destination Member States need to coordinate better to ensure that catch certificates for seafood imports are effectively scrutinised and that robust monitoring and import controls are applied consistently across the whole length of the EU border, smaller countries included. An EU-wide IT system to facilitate the harmonised, coordinated and risk-based monitoring of seafood imports across the EU is pivotal to the success of the IUU Regulation and its establishment must be a priority task for the European Commission and Member States alike.

*The Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), Oceana, The Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew) and WWF are working as a coalition to secure the harmonised and effective implementation of the European Union’s Regulation to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.